The American Fly Fisher, the renowned quarterly journal published by the American Museum of Fly Fishing, has published an essay written by Robert Reid. Titled ‘A River Runs Through Tom Thomson,’ the essay argues that Canada’s legendary visual artist and spiritual guide of the Group of Seven was not only a fly fisherman but might well have tied flies to match the hatch.

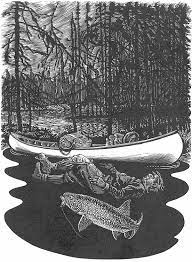

The essay, which spans eleven pages as the Spring 2022 issue’s feature contribution, is based on a chapter in Reid’s memoir Casting into Mystery, published by the Porcupine’s Quill in 2020 and featuring wood engravings by master engraver Wesley W. Bates. Reid published an earlier version of the essay in 2017 and posted it on his blog www.reidbetweenthelines.ca

Combining extensive research and his understanding of fly fishing, both its history and its practice, Reid discusses Thomson in a historical context of fishing in the early years of the twentieth century when the artist spent some of each consecutive year from 1912 through the summer of 1917 in Algonquin Park, where he unexpectedly and suspiciously died on Canoe Lake. An avid fisherman, he sketched and painted in the park, and served at various times as a park ranger and fishing guide.

Some of the commentators mentioned below refer to Roy MacGregor, the prominent Canadian journalist and author who wrote Northern Light, in which he cast doubt–in very condescending, and patronizing language–about Thomson being a fly fisherman. The seeds of my essay, which grew over time like branches of a river, were planted as a critical rebuttal to MacGregor.

The essay–which features Thomson’s most accomplished angling painting, archival photographs and a couple of Wesley Bates’s wood engravings including a haunting death portrait of Thomson–has been well-received within the international fly angling literary community.

Keith Harwood, a prominent British angling historian, author and editor (The Hardy Book of the Salmon Fly, Tight Lines: The Story Abu, Fish & Fishers of the Lake District, Sir Walter Scott on Angling, John Buchan on Angling and The Angler in Scotland, among others), praised the essay.

In an email to the journal’s editor, Kathleen Achor, he noted that he ‘was delighted to read (the) article on Tom Thomson. Please pass on my congratulations to (Robert Reid.) He makes a very convincing case for Thomson being a fly fisherman and a slightly less convincing case for him being a fly dresser. . . I am a great fan of (Thomson’s) work and the Group of Seven and have several books on their work. Over twenty years ago my wife and I saw a wonderful exhibition of their work in the Art Gallery of Ontario during a visit to Toronto.

In many ways (although their styles are completely different), Thomson reminds me of the British Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir John Everett Millais. Like Thomson, Millais was a passionate angler who often fished with Rupert Potter, father of Beatrix Potter, on the Tay, and, like Thomson, rarely painted a fishing picture. A couple of years ago I wrote an article on Millais for Classic Angling magazine.’

Henry Hughes, a prominent American angling historian, author and editor (Back Seat with Fish and Everyman’s Pocket Classics’ Fishing Stories and The Art of Angling: Poems About Fishing) also praised the essay.

‘Forgive the long silence–just busy with school, editing–and some fishing,’ he wrote in an email. ‘I wanted to say how much I loved your article on Tom Thomson. Of course, I remembered it from Casting into Mystery, but it seems you added a bit, and the images and layout are very fine. The American Fly Fisher offered you the classy showcase your work deserves. Keep up the great work, sir.’

Closer to home, in Southwestern Ontario, Doug Wilson, president and CEO of the Cambridge Butterfly Conservatory and a longtime angler, offered a profusion of kind words.

‘You are an elegant writer, Rob,’ he wrote in an email. ‘You have done something remarkable, blending critical argument and exhaustive research with (angling) lore–and doing so in a manner that is downright engaging. Fly fishing is art and art is in the casting of a fly line, and this essay firmly establishes this fact. And what better vehicle than through the story of Tom Thomson. I can’t imagine the amount of time you spent researching this piece. But look what you have accomplished.

‘I loved the essay, more accurately I loved losing myself in the essay. I will tell you that, when we bought our first computer and finally connected to the internet (via dial-up), the first thing I did was sign up for an online membership with the Boston Museum of Fine Art because, at the time, it had a superb collection of Winslow Homer’s work. I spent hours when the kids were in bed leafing through the paintings (back then it took hours for the images to load).

‘In 2002 I travelled to Ottawa to see a retrospective of Thomson’s work at the National Gallery. The poster still hangs in our kitchen. I got emotional when I came upon his paint box in a display case. So, the connection you draw between these two revered artists means a great deal to me and I can imagine it will resonate with anyone who reads your essay, anyone who has an interest in art and in fly fishing.

‘When I read your essay the same thing happened that happened when I looked at those paintings. You gave me permission to let my mind wander and dream of Northern streams and the sun on my face and the scent of cedars and the spring song of Chickadees. But, most importantly, it’s the argument you so eloquently put forth establishing Thomson as a fly fisher that will put the nonsense of his not casting a fly line to bed once and for all. (Why do you suppose Roy MacGregor has such a problem identifying Thomson as a fly fisher?)

‘Your essay will no doubt find its way into the hands of many readers and firmly establish you as a critical essayist extraordinaire. I am so grateful to you for the chance to read this essay. I can now slip it into a protective cover to be pulled out and read and re-read as the soul requires.’

Doug Kirton is a longtime practicing artist and associate professor in fine arts at the University of Waterloo, where was recently department chairman. Although new to fly fishing, he offers a perspective that combines love of the contemplative recreation with knowledge of painting and art history.

‘Your article is totally convincing on Tom as a fly fisher,’ he wrote in an email. ‘I think those of us who understand (art and fly fishing), know this for sure. In the broader picture, your article goes a long way in promoting a deeper understanding of Canadian history in general, especially the references to our music and literature. You’ve done a great service to the arts in Canada.

‘You strengthen your argument from all directions: the Audrey Saunders part is particularly solid testimony. Has Roy MacGregor seen the chapter in Casting into Mystery? If not, I wonder what his reaction to the American Fly Fisher article will be? And did you send a copy to the British guy (director Ian Dejardin) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection? I hope he reads it slowly and carefully!

‘I agree that The Fisherman is Tom’s most lucid figure painting. There is a grace about the gesture that makes me think he worked from a photo for reference, just because it’s so specific, and as we know, Tom wasn’t noted for his figurative skills. However, his training as an illustrator and graphic designer would have honed his visualization skills . . . so who knows? I must admit to still being a little troubled by the straight rod. When did nymphing (as opposed to dry fly fishing) come to Canadian fly fishing? Could the straight rod be high sticking?

‘As for Tom’s expertise in the woods: I’m sure he was more than qualified. But I’m also intuitively sure that he would have faced opposition from the residents (in Algonquin Park). These guys built their lives around their reputations and would have perceived Tom as a challenger.

‘I thoroughly enjoyed your essay, Rob. It fills in a lot of historical detail with credible evidence of Tom’s adoption and innovations in fly fishing.’

Doug Kirton is right to raise questions about the straight rod the fisherman is holding in the painting. All accomplished angling artists, including Winslow Homer, are careful to depict accurately bent or arching rods when anglers are playing fish in their pictures. However, if I am correct in my essay about the rod representing a magical staff or a wand, the lack of throbbing arc is understandasble, if not completely convincing. I can find support for my interpretation.

No less an authority than Norman Maclean a couple of times in A River Runs Through It has his narrator Norman describe his brother Paul as ‘a man with a wand in a river, and whatever happened we had to guess from what the man and the wand and the river did.’ (Italics mine) Similarly, John Gierach, arguably the most popular contemporary fly angling writer in the world, titled one of his essay collections Standing in a River Waving a Stick–note: not rod or even pole, but stick.

Chris Pibus is in the process of retiring from his Toronto-based legal practice as one of Canada’s leading Intellectual Rights experts. He’s a lifelong fly angler who has fished widely throughout North America and Britain. He has deep knowledge fly fishing, literature and the visual arts.

‘I am so impressed with this piece–I think it is outstanding, surely one of the best essays ever written about Tom Thomson (and angling),’ he wrote in an email. ‘And one of the best I have ever read on the intersection of art and biography and angling. Brilliantly argued. Roy MacGregor is now truly done and dusted. It is worthy of multiple re-readings which I shall do.

‘I have looked closely at the painting of The Fisherman and I agree it’s critical to your argument. Two things I notice.

‘First, there is a huge honking brook trout lying on the rock at his feet–it could be a twenty incher– and he put it there like any proud fly fisherman as a testament to his prowess and proof that fly rods and small flies can be deadly on big trout. He is portraying himself as a powerful figure who is a master angler–as you say this must have been a big part of his identity.

‘Second, the way he has painted the figure is very interesting to me. He has given himself a powerful pose and his arms look massive. What is striking is the composition of his arms; that is where your eyes go when you look at the canvas. Together the arms form a big circle–he looks like he is embracing the natural world like this is his chosen place of glory. Or maybe I am getting carried away?

‘You should be very proud of this, Rob. It’s a real achievement: original thinking right down to its bones.’

Chris Pibus’s astute observations about Thomson’s depiction of the angler’s arms reminded me of Norman Maclean’s haunting description of his brother Paul in the final few pages of A River Runs Through It when Norman’s artistry transforms his brother into a mythic figure who, like all things, ‘merge into one, and a river runs through it.’ I have always viewed Maclean’s novella as starting out as a Wordsworthian celebration of pastoral nature and ending as a Blakean celebration of mythic man at one with mythological nature.

Here is Paul, casting not as a man, brother and fisherman but as an emblem and a symbol of the Universal Fly Angler, transcending time and place including the timeless and most distant place of all–the human imagination, heart and soul:

‘As he waded out, his big arm swung back and forth. Each circle of his arm inflated his chest. Each circle was faster and higher and longer until his arm became defiant and his chest breasted the sky. On shore we were sure, although we could see no line, that the air above him was singing with loops of line that never touched the water but got bigger and bigger each time they passed and sang. And we knew what was in his mind from the lengthening defiance of his arm. He was not going to let his fly touch any water close to shore where the small and middle-sized fish were. We knew from his arm and chest that all parts of him were saying, ‘No small one of the last one.’ Everything was going into one big cast for one last big fish.’ (Bold mine).

Chad Wriglesworth, associate professor in English at St. Jerome’s University College at the University of Waterloo and editor of Distant Neighbors: The Selected Letters of Wendell Berry and Gary Snyder, takes a big-picture view of publication in a museum journal.

‘I really like your self-awareness about contributing to the field of writing/study,’ he said in an email. ‘Honestly, the longer I do this sort of thing, the more I realize that making that contribution is really what this is all about. In the long run, the idea of writing for one’s sense of ego just turns out to be worthless. None of us will survive to see any kind of end to any of this conversation (whatever field a person is working in). So, it becomes a matter of stewardship and contribution–contributing those small and satisfying parts to a very large and always emerging whole.

‘Anyway, wonderful news all around. I’m delighted to see your article in the American Fly Fisher. In my experience these museum and historical society publications always tend to be classy and so well put together. About ten years ago, I published an essay with Columbia, which is put out by the Washington State Historical Society. It is still one of my favourite publications–the layout, editing, accompanying visual materials were just bang on.’