‘Are you up for an outing on the West Branch?’ I had written Chris Pibus in an email.

I wasn’t referring to the legendary West Branch of the Ausable, in the Adirondacks, or to the West Branch of the Delaware, in the Catskills, but rather to a modest stream feeding a Heritage River in southwestern Ontario.

‘Absolutely,’ he replied. ‘What day works for you? When can we meet?’ A subsequent exchange of emails set our plans into motion.

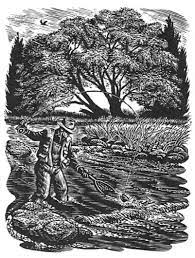

All my closest fly angling companions visit this trout stream early in the season. We’ve all enjoyed various degrees of success, so we return season after season with high expectations. Chris and I, however, are the only ones–so far as we know–who dedicate time and effort to what we have come to call the West Branch. It’s our little secret.

Most anglers have secret fishing spots. It’s an enduring piscatorial trope. Anglers often go to ridiculous lengths to protect the identity of these sacred places. If you don’t believe me, read and relish accounts of the antics recorded by the great angling scribe Robert Traver, who dreaded angling interlopers in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula as if they were carriers of a highly infectious disease.

Occasionally angling companions surreptitiously share a mutual fishing spot after swearing an oath of secrecy. They have good reason to fear the location being uncovered or revealed, either unwittingly or deliberately. A broken pledge opens a door that cannot be closed and through which unwelcome anglers traipse bearing avarice in their hearts coupled with lapses of good sense and conscience.

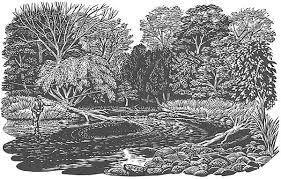

The curious thing about the secret Chris and I share is that the fishing doesn’t really warrant such confidentiality; evidence accumulated over subsequent seasons confirms it’s less productive than the most generous parts of the stream we all fish in common. In all the times we’ve fished it together, I only once hooked a big brown trout. I was too excited–maybe even shocked–to land him. Sure, the West Branch has its beauty spots, but overall it’s no more picturesque than the rest of the stream.

Why Chris and I guard our secret so tenaciously is anyone’s guess. I have no answer to advance. Still, I suspect it might have something to do with the child-like quality that fly anglers of a certain age seem to possess. Most remember when they were young and had a secret hideout or clubhouse, a retreat, and sanctuary shared with a small select group of friends, compatriots, comrades or confidantes. It’s what boys do–I certainly did. After all, nothing appeals to the imagination like intrigue and benign forms of conspiracy.

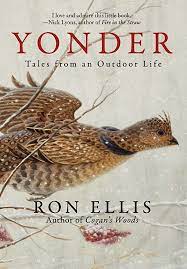

NOTE: I have long believed that a writer’s best friend is serendipity–or, a better word, synchronicity. As I was pausing between drafts of this essay I came across a term, heart ground, in Yonder, a collection of personal essays by the fine Kentucky outdoor writer Ron Ellis. He coined the evocative term to describe the ‘sacred ground’ where hunting converges with ‘dogs and friendships.’ It occurred to me that the term heart water can be applied equally to fishing. As I now reflect on the secret of the West Branch that Chris and I share I believe it was inspired by our mutual sense of heart water.

. . . . . . .

I’m a lucky man. One reason is because I have half a dozen companions in what I call a Fellowship of Literary Fly Anglers. I don’t intend this phrase to sound pompous or fatuous. An angler could not find finer friends with whom to share time on the water than Dan Kennaley, Wesley Bates, Doug Kirton, Doug Wilson and Chris.

For them to be accepted in the Fellowship, however, they must read books with as much enthusiasm as they fish. Although our literary tastes vary and we read in subtly different ways, we all agree that fly fishing literature has a long, diverse and rich tradition superior to the writings devoted to any other sport or recreation.

Moreover, we agree that angling books enhance and enrich experiences on the water, much as experiences on the water enhance and enrich reading. For example, I enjoy hosting occasional book club meetings in which the Fellowship convenes for lively discussions about such works as Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, Ernest Hemingway’s ‘Big Two-Hearted River’ and Ted Hughes’s suite of poems River.

My luck was compounded when I met Chris as a result of my memoir on fly fishing. He decided to reach out after reading Casting into Mystery shortly after it was published early in 2020. We exchanged emails and agreed to meet on the shoulder of a country two-lane hardtop near the Grand River for an evening of bass fishing. One of the things Chris learned from my memoir is that we share an important thing in common. Like my son Robertson, Chris’s son Nat is on the autism spectrum. Chris also has a daughter Caitlin and I have another son, Dylan.

Chris has fly fished since adolescence. He has travelled to many prominent angling destinations throughout Canada and the United States, in addition to Britain, whenever he managed to break away from a busy legal practice as one of Canada’s top intellectual property lawyers. As I write this essay, he has visited Alberta’s Bow River and the legendary Delaware River within a few weeks of one another.

In addition to his worldly travels, Chris has been an occasional visitor to the Grand, which I consider my home water. We shared such a pleasant time on our initial outing we agreed to meet again. He was so impressed with the stretch of river that he returned a few days later with Nat on one of their regular weekend walks. They christened the location Rob’s Pool. (I was moved when Chris relayed this story.)

Since then, we have fished many times together for bass on the middle Grand and trout on the tailwater, in addition to a productive tributary we especially like. I have also introduced Chris to my favorite southwestern Ontario headwaters which, thankfully, sustain populations of brook trout—at least for now. We soon developed a custom after returning to our vehicles wherein I provide Swedish wild berry cider to complement Portuguese custard pastries Chris buys fresh from his favourite neighbourhood bakery.

Chris is a careful, attentive, methodical, generous fly angler with a keen eye for places where fish like to hang out. He seldom leaves the water without landing a few. Still, when fish refuse to cooperate, he harbours neither grudges nor ill feelings.

While I prefer dry flies and swinging nymphs and streamers downstream and across, Chris prefers high sticking nymphs when he isn’t casting dries. Unlike me, he ties his own flies, having met such legendary tiers as Fran Betters over the years. However, his tying isn’t as obsessive as it is for many anglers who have been fly fishing for as long as he has.

I was delighted to accompany Chris when he landed a beautiful brown trout on water in which they are much less common than more abundant rainbows. Conversely, he witnessed my landing of sixteen smallmouth bass within a couple of hours on the Grand. We also fished the tailwater on a memorable occasion when I caught nine brown trout before encountering a pair of beavers—man, were they big–on our way back to our vehicles.

Chris is one of the most literary members of our Fellowship of Literary Fly Anglers. Like me, he has a master’s degree in English literature, which he attained while completing a law degree from the University of Toronto after graduating with a bachelor’s from McGill, in his native Montreal. He comes from a family of teachers, a generation removed from farms in Quebec’s Eastern Townships. I find this interesting because, of the many lawyers I met over a forty-year newspaper career including stints as a crime and court reporter, Chris strikes me as the least lawyer-like and the most teacher-like, even professorial, of the lot.

Although I suspect Chris was prepared to access a tough and resilient resolve when needed in his professional life, his nature is quiet, reserved and gentle—even patrician. He exudes a sense of gravitas without seeming to exert any effort. This is balanced with a love of storytelling shaded with wit and humour. I know from our many discussions about books, not to mention the books we’ve recommended to each other and exchanged, that his literary knowledge is as deep as it is wide, astute as it is enthusiastic.

It gives me deep delight to know that Chris and his wife, Penny, honour a ritual of reading favorite books aloud—which I uphold as a gesture of love. Childhood sweethearts who met in elementary school, started dating in high school and are still together more than a half century later, they have just completed Robert Fagles’ celebrated translations of Homer’s Odyssey and Illiad.

Generally fly anglers take one of two approaches when fishing with a companion. Either they go their separate ways, agreeing to meet up at a specific place, at a specific time; or they accompany one another on the water. Most often Chris and I choose the latter. Again, there are two general approaches. Either the anglers remain quiet for the most part, concentrating on the task at hand. Conversely, companions are downright chatty, which describes Chris and me. No topic is off limits when we are casting lines on the water.

Fly anglers almost always share common interests, but oftentimes fall short of seeing eye to eye–or, should I say, cast fly to fly-when it comes to values. Chris and I don’t have that problem. I feel like we were destined to become friends and angling companions.

Regardless of our wide topics of discussion, books are never too far from our conversation, whether gearing up, casting on the water, resting momentarily on a bankside log, removing our gear or enjoying a late supper. Of course some of our book talk focuses on angling literature, but not all. We share many favourite authors and some favourite national literary traditions including Irish, Canadian and American. We take great delight in comparing our experience of a book we have read recently to our experience of reading it as young men.

Neither Chris nor I have examined our conduct on the water extensively; however, I have a strong sense that we approach fishing less competitively than some of the other anglers comprising our Fellowship. Don’t get me wrong; Chris likes to catch fish as much as I do. After all, while we both believe that fishing is about more than catching, we agree that never catching any fish isn’t really fishing either. It’s an exercise in escapist masochism masked as benign futility.

Still, when all is said, we share the belief that books and companionship are important and vital to fishing. For me, they are as significant as catching fish. And I know Chris feels much the same way, despite his half century of casting artificial flies.

I know this because, since his reluctant retirement, Chris has embarked on an exciting creative journey of transforming his most memorable experiences on the water into autobiographical stories of deep feeling and uncompromising merit. Most involve companionship in one form or another.

I’ve enjoyed accompanying Chris on his literary journey as a sympathetic first reader and editor. He has repaid me the compliment by playing the same role in what the beloved Canadian writer W.O. Mitchell called a creative partnership. In the first year of retirement he has had essays accepted for an anthology of Montana nature writing and for the American Fly Fisher, an esteemed journal published quarterly by the Museum of American of Fly Fishing. I eagerly anticipate publication of some of his essays and stories in a book.

. . . . . . .

The frustration inherent in fishing is that anglers can’t always count on catching anything. It so happens that the last time Chris and I visited the West Branch our best intentions were hijacked by water flow conditions beyond our control.

Granted we weren’t optimistic after arriving streamside at the apex of July. In contrast to much of the world which had recorded historically high temperatures causing extensive drought and wildfires, Southwestern Ontario had received substantial rainfall during the previous few days. So, it wasn’t unexpected when a cursory examination from a bridge overlooking the stream verified elevated water levels.

Anglers put their faith in hope with the desperation of addicts craving the next fix. Burton L. Spiller muses on this affliction of optimism in Fishin’ Around when he writes, ‘There is, I think, some merit in looking on the negative side of a forlorn hope, for in summing up the possibilities of failure one stands an infinitely better chance to succeed.’ Accepting Spiller’s advice, we gamely agreed to defy probability and investigate the West Branch. After slogging through tall, tangled, overgrown vegetation and negotiating a series of spider-webbed canopies, we crossed the magical portal to the stream.

Not surprisingly, but no less disappointingly, it was too high for us to safely traverse the ten metres to the other side, from which we customarily commence casting. We hummed and hawed, compared notes, and finally, with no reasonable option before us, turned around and trundled back with our fly rods tucked between our legs.

In momentary weakness, we reviewed the prospects of calling it quits. Then we reconsidered and decided to test our fortune on the section of stream we generally fish with our other angling companions. Although pleasant enough, it didn’t reward our aspirations. Chris landed a small rainbow in an inviting run, while I came up empty handed—in a word I was skunked.

After ninety minutes of futility, we hightailed it to a favourite pub boasting a charming view of the Grand River in a nearby town. As usual we ordered plates of Lake Erie perch and chips with homemade coleslaw, washed down with a chilled pint of craft ale for me and an Arnold Palmer (a combination of lemonade and iced tea) for Chris. And good conversation. In contrast to the wily fish we pursue with fly rod and reel, we can count on good conversation–always.