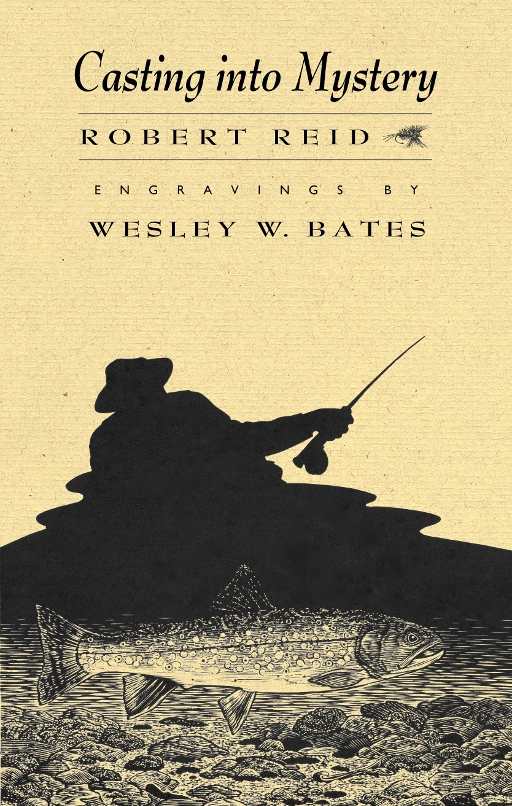

I am a terrible fisherman. It has been years since I caught a fish (though not for lack of trying) and I have never attempted fly fishing myself. So, when I sat down to read Casting into Mystery, written by Robert Reid with engravings by Wesley W. Bates, I found myself in the role of a delighted student, and this book proves an excellent teacher. The main lesson I took away from my reading is that Reid and Bates both view fly fishing as a gateway to many aspects of the world. Whether it be books, music, philosophy, religion or love, everything can be related back to the hours they spend standing hip deep in the river.

While I may not be an expert fisherman who has spent hours standing in rivers, I am familiar with poetry and language, and Reid’s mastery and deep love of these allows him to convey why fly fishing is for him such a special and deeply personal pastime. He draws connections between fishing and art, rivers and mystery, nature and philosophical contemplation, allowing me to attain an understanding of the sport that had previously eluded me. Fly fishing as described in this book is an action that allows one to challenge oneself, allows one’s mind to be set at ease (which subsequently allows it to wander and ponder), allows one the opportunity to be social while alone, and sets nature as the inspiration for art.

Reid is not the first writer to connect nature and sport to art. Going back to classical literature, we see countless examples of hunting tales and pastoral imagery that are designed to speak to the reader about art. Further, there are countless mosaics and other pieces of art which depict natural scenes or scenes of the hunt. These two concepts are inseparable. So, while Reid’s use of nature and sport to engage with art is not revolutionary, I have never seen anyone approach this through fly fishing.

Reid is clearly not alone in feeling this connection. A self-proclaimed avid armchair angler, he notes that many writers before him use fly fishing as their muse. The essays “Books for a Winter Night” and “The Poetry of Fly Angling” detail some of Reid’s favourite authors to read when he is not on the river. These include fictional works, usually in the mystery genre (by the likes of David Leitz, Victoria Houston, and his personal favourite Keith McCafferty), poetry (Raymond Carver, Ted Hughes, Jim Harrison and John Engels), and non-fiction discussing everything from casting technique (Tom Rosenbauer) to fly tying (Patterns of the Masters) to travel literature (Betters’s Fishing the Adirondacks) to philosophy (David Henry Thoreau). This is quite the comprehensive literary examination that Reid provides, and he centres it entirely around the topic of fly fishing.

While literary discussions abound in Casting into Mystery, showing the intersection of literature and nature, I think the essay that best exemplifies Reid’s deep bond between art and fly fishing is “A River Runs Through Tom”. In this essay, Reid argues that the famous Group of Seven painter Tom Thomson was a fly fisherman himself. Evidence in favour of his argument aside, the passion that Reid displays here in drawing a connection between artist and sport, as well as his art and the nature that surrounded him, drives home Reid’s fundamental belief: fly fishing is a medium through which one interacts with their world and the art they enjoy. In Thomson, we see the embodiment of this belief. That his engagement with nature through canoeing and, as Reid argues, fly fishing, directly contributed to his art. I must admit it is a very persuasive argument.

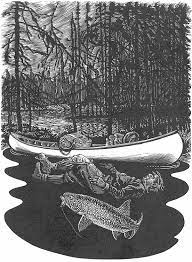

Reid has not created this book alone, however, and I would be remiss if I did not mention Bates and his engravings. Like Reid, Bates is an avid fly fisher himself, and his personal relationship to nature and art comes through in his engravings. Beautifully detailed and often requiring many viewings to appreciate their full depth, these engravings serve as highlights to Reid’s words but also as narratives in their own right. While Reid discusses the relationship between nature and art, Bates puts it into practice. I found the engraving of Thomson particularly striking. Depicting the mystery of his death in Algonquin Park in 1917, it is suitably grim with an air of solemnness–a perfect fit for the essay and wider themes of the book.

Just as the rivers that Reid and Bates are so fond of meander, so do the musings of Reid and the carving tools of Bates as they explore in their separate but interrelated ways what it means to be a fly angler, an artist, and ultimately what it means to be uniquely human. Each manages to capture in is own way the intersection of nature and art, and each allows us as readers to experience a very personal connection to both. Hopefully by having read this, I will become a better fisherman myself, but that seems unlikely. And, as Reid says, “ If I fly fish and don’t catch any fish, I still win” (189).

— Review posted on the Porcupine’s Quill website blog on 19 April 2021 by James Bader. A Masters of Arts in Classics graduate from McMaster University, he lives in Dundas, Ontario where he is a supply teacher at Lee Academy elementary school.