Fly anglers well versed in the ways of trout agree that stealth is a path to success. If you can see the trout, the trout sees you, goes the warning.

As a result, anglers exercise caution when wading–no noise, no disturbing wake, no stumbling and bumbling that kicks up riverbed detritus. Anglers are careful not to cast shadows that alarm wary trout. Blending in is the ticket, including inconspicuous clothing. I have heard that some anglers worry their silver- or gold-plated reels give them away. I have also heard that some anglers reject brightly coloured fly line for the same reason. Anglers cast gently so as not to arouse suspicion and trigger fear—artificial flies must fall on the water like whispers on the wind.

This advice makes abundant sense if the objective is to catch fish. But what if catching fish is not the only goal? What if a large part of the reason for fly fishing is connecting with nature, establishing a bond or kinship with fellow creatures with whom humans share this good green earth?

If William Shakespeare is right—if ‘eyes are the window to [the] soul’—is eye contact between angler and trout such a bad thing? Is it to be avoided at all cost? Or does the experience of profound intimacy, of deep connection, have value—at least for the creature holding the fly rod? Or is such fancy or whimsy akin to angling heresy?

I started musing about eye contact with trout while reading Harry Thurston’s A Place Between the Tides. Subtitled A Naturalist’s Reflections on the Salt Marsh, the memoir records recollections of his childhood farm life after he, his wife and daughter move to the Old Marsh on the banks of Nova Scotia’s Tidnish River. I came to the book after reading Thurston’s more recent book Lost River, subtitled The Waters of Remembrance. I think of it as A River Runs Through It meets The Mountain and the Valley. I was deeply impressed with his angling memoir and was delighted to discover that I had his earlier offering in my library, which like the later book is about memory, family and nature, written with both beauty and grace. Although I had not set aside time to read it, I quickly remedied the oversight. Needless to say, I enjoyed the book immensely.

In A Place Between the Tides Thurston references theologian Gary Kowalski’s book, The Soul of Animals, which posits that humans come closest to touching the inner lives of other animals through the eyes. In his celebrated book Kowalski argues that animals are not insensitive creatures devoid of feeling and intellect but thinking, sentient beings with an inward, spiritual life. Thurston riffs on this theme by recalling a close encounter he experienced with a red fox, which he named White Face, who for a number of years raised a family in a den close to his house.

This got me contemplating four separate instances in my life when I had intimate encounters with wildlife.

The first instance also involved a red fox, one in a leash that lived most of a year in a small copse of conifers and hardwoods behind my apartment. On one of my daily evening walks I came across three young ones cavorting like exuberant puppies. Two ran off upon my arrival, but one stayed behind. He/she stared a me for what seemed like long minutes, rolled over a few times, sat on his/her haunches, stared at me, scratched his/her ear, rolled over a few more times, sat again on his/her haunches and stared at me yet again. I have had dogs most of my life (a spaniel, a rough collie, a Lab and a pair of Labradoodle sisters) and to me this was an invitation to play, pure and simple. He/she did not move off until a car sped by, breaking the spell. Regardless, I can recall thinking at the time that we had established a meaningful bond, if only momentarily.

by Wesley W. Bates to illustrate a poem by Gary Leitz (Larkspur Press)

The second instance involved one of nature’s most incredible birds. I was sitting on the porch one afternoon enjoying a cup of coffee when a ruby-throated hummingbird swooped down and darted toward the feeder in anticipation of some sweet concoction. Instead of sticking his/her long slender beak into the red and yellow tulip-shaped receptacle, he/she turned and stared at me for what seemed like an unusually long time. At first I thought he/she might be getting a reflection off my eyeglasses. Regardless, he/she remained in stationary flight pattern before dipping into the receptacle and darting off. Again, the experience made me think I had bonded with the critter.

The third instance involved one of nature’s most awesome birds. It happened when I returned home from an afternoon of canoeing with Lois Hayward, my partner at the time. I was sitting on the porch enjoying a cold beer when a peregrine falcon swept onto a branch and perched in a Norway maple in front of me. He/she was magnificent. We exchanged stares—his/her piercing eyes seemed to burrow into my eyes—for a good five or ten minutes. I knew it was a falcon because I had read in the local paper that a pair had nested atop the twenty-storey Sun Life Financial headquarters, located on the boundary of Kitchener and Waterloo, no more than a mile or two, as the falcon flies, from where I was living. It was amazing; it actually gave me chills. Again, I felt as if I had bonded with another creature.

Of course, this is not unusual, my friend Sherry Wolf has regaled me with tales of intimate confrontations she has experienced with both deer and coyotes while walking in a forest close to her home. Her two male shih-poos, the tenderhearted Miko and the feisty Hagrid, have had similar experiences with deer he seems determined to befriend, suggesting that this is a common cross-species experience.

Before any reader gets the erroneous impression that I am advocating some sort of anthropomorphic Bambi meets fly angler in the Wonderful World of Disney, let me stress that an encounter with the wild is fraught with potential danger, as Sherry well knows. Here is a series of texts, not uncommon by any stretch, detailing a confrontation with a pair of coyotes:

‘Ran into two coyotes in the forest at 6:30 pm., They followed us. I came around a corner [on the path] and both dogs took off like maniacs. I thought it was a deer. Then I saw his tail. I put the dogs on leashes and threw big branches and large sticks at him as he sat about ten feet away, staring.

‘So there we were,’ she continues. ‘Crap, I thought, there must be another one behind us. And, sure enough, there she was two feet away. She did not budge, sat perfectly still. When I threw a large stick at her, she just smelled it and stared at us. So I had to back up out of the forest holding the boys on leashes and carrying a big stick.’

A day later she received this text from a mutual friend who was walking his dog in the same area in the forest.

”Just returned from a walk [about 3 pm] and had a close encounter with aggressive coyotes. Charged at us with teeth bared. Didn’t follow but watched us for awhile. Think they have a den in the area.

Wesley Bates tells of an encounter he had with a red-tailed hawk that habitually cruised the Hamilton neighbourhood where he lived at the time. ‘I think it had an aerie in the Catholic church steeple a block over from my third-floor apartment,’ he said. ‘I witnessed him take a pigeon in mid-flight and devour it on the top of a streetlight pole just ten feet from my window. The hawk gave me a good look over as I gawked at him.’

It just so happens I was reading Le Anne Schreiber’s Midstream, her ‘intimate journal’ of loss (death of her mom) and discovery (moving from New York City to a century home in the country and taking up fly fishing) when I was writing this story. Schreiber recalls walking on a nature trail and confronting a whitetail buck that ‘stood his ground.’ ‘Staring straight’ at one another in a mutual ‘glare’ for ten minutes or so, he eventually bounded away, leaving Schreiber in a state of exhilaration. She confides that, for the first time in her life, she felt ‘an animal was treating me like a fellow creature.’ YES, that’s it, EXACTLY!

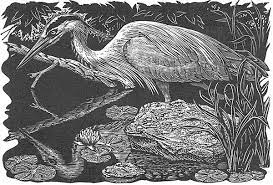

The final instance of intimate contact took place on water and unfolded as a prolonged dance between me and a great blue heron. One evening I was fishing the Grand River tailwater for hatchery raised brown trout. Unlike some anglers who view herons as a predatory threat to fish stocks, I admire them as minimalist precision anglers who feast on small fish. I view this as natural adaptability and selection; survival of the fittest in its most elegant form.

by Wesley W. Bates in Casting into Mystery

Of course, herons are pure stealth. They stand absolutely still, like a blade of tall grass on a windless day. They patiently wait for a meal to swim within striking distance of their S-shaped necks which, like coiled springs, are unleashed at high speed in the blink of an eye. After spearing their piscine morsel, they lift their heads back to swallow, with great shakes of apparent satisfaction to assist digestion.

On this evening the heron played out this ritual repeatedly, leap-frogging over me whenever I passed him/her while casting mid-river as I diligently made my way upriver. We continued this dance as two partners too shy to embrace, but eager to keep moving in syncopated rhythm, for more than an hour.

What does this have to do with fly fishing? Thurston speculates in A Place Between the Tides that the boundary between ‘watcher’ and ‘watched’ is fuzzy, that animals watch humans as much as humans watch animals. This natural bond or kinship complicates the relationship between predator and prey, even when applied to anglers and trout. If this is true in the complex web of life, then I believe humans have a moral obligation to respect all species other than themselves. This implies a reciprocity of ethical responsibility anglers are obliged to assume when fishing for trout—which applies equally to all anglers and to all species of fish.

I am not advocating that fly anglers avoid or discard all tactics designed to assist in the catching of trout—or of any other species. Only that they open their minds and hearts and imaginations to seeing nature in all her complexity and fragility and vulnerability. With this visionary perspective comes acceptance that anglers are not separate and apart from nature, but are threads woven into the intricate fabric of all living things.

In this way fly fishing, to paraphrase the Bard, holds ‘a mirror up to the Mystery of nature.’