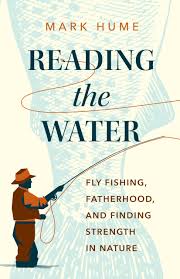

Reading the Water

by Mark Hume

Greystone Books

276 pages

The worst blasphemy routinely hurled at fly fishing is reducing it to a sport, hobby or pastime. But don’t take my word for it. Instead, consider Mark Hume’s Reading the Water. Subtitled Fly fishing, Fatherhood and Finding Strength in Nature, it’s not so much an angling memoir as an account of life lessons learned through the wisdom of fly fishing. Admittedly this might sound highfalutin to anglers who doubt Hume’s claims. All I can say is: read the book and then judge.

Hume was born in British Columbia, the middle of five sons of English immigrants who were practicing Christadelphians (a sect disavowing selected Christian orthodoxy). His parents met during the Second World War when his mother was a member of the Women’s Land Army and his father was interned as a conscientious objector. They married after the war and moved to Western Canada.

Following his father’s example, Hume has lived most of his life in British Columbia as a journalist on some of Canada’s most respected newspapers. The province has produced numerous angling writers of merit including English-born Roderick Haig-Brown. I believe Hume—who has written four angling books built on environmental themes including River of the Angry Moon and Trout School—is the rightful heir to Haig-Brown. Hume’s knowledge of angling and ecology is extensive; however, it’s the eloquence and grace of his prose that inspires comparison to the writer he honours as ‘The Master.’ To prove my point I quote a lengthy passage that demonstrates Hume’s narrative gifts while capturing the essence of Reading the Water:

When I became a father I knew I would guide Emma and Claire along riverbanks, show them how to wade on rocks worn smooth by fluvial erosion, teach them how to read the water and how to cast with elegance. Those lessons of technique would be relatively easy to give, but I didn’t know if a love of fishing, which had fallen to me as a kind of natural inheritance, could be taught. I thought it important to try, however, because fly fishing for me had become a way of navigating life, and I wanted that for them too. Through an absorbing involvement in nature, fly fishing fosters resilience and inner strength. It can help make a person whole. I felt my daughters should know that, though I wasn’t aware at the beginning of our journey how much teaching them to fish would help me; how I would draw strength from them too.

Hume’s ‘bond’ with fishing was forged when he was seven years old on a mountain stream where he ‘found trout that seemed to be always waiting for me.’ Thereafter he ‘never stopped searching in water, not just for hidden fish but for answers, for emotional renewal and strength.’ Years later, after his daughters were born, he was confident that the knowledge he had learned through ‘the intricacies, rituals and poetry’ of fly fishing could be shared with others.

Like all good teachers who eventually realize they have learned as much from their students as they have taught, Hume fulfilled the role of mentor by holding onto the belief that, ‘fly fishing is an intensely observational way of experiencing the world and, in that sense, is a spiritual experience.’ Like Norman Maclean in his sacramental A River Runs Through It, Hume observes that the ‘powerful connection’ between faith and water is a form of ‘reverence for the virtues of nature’ that awakens ‘an awareness of what it means to fit in to the universe.’ Casting a fly rod is ‘a state of grace’ that instills in anglers an appreciation ‘that there is something wonderful, magical, revelatory about drawing fish into light’.

I quote generously to rebut anglers who view fly fishing as nothing more than one of any number of ways to catch fish. Equal parts spiritual autobiography and ethical treatise, Reading the Water follows a long tradition from Dame Juliana, through Sir Izaak, to Haig-Brown. As such Hume portrays fly fishing as a path towards awareness of both inner self and outer world with its concomitant responsibilities and obligations:

In my short lifetime I have seen great rivers dammed, entire forests clearcut, species pushed to the verge of extinction and the planet compromised to the point of becoming threatening. And yet, there on the water, reaching down to touch cold-blooded fish, I have always found hope. As my daughters awakened and began to see the Earth changing, I knew they would need that kind of connection to nature if they were going to have faith that the planet could be saved—and restored.

Reading the Water begins as a shaggy Huckleberry Finn adventure tale chronicling Hume’s introduction to various wood scenes and riverscapes that accommodated his piscatorial apprenticeship from catching trout barehanded, through bait with bobber and spin casting, to fly fishing, as his family moved from the fertile Okanagan Valley to the high plains outside of Edmonton and back to the lush majesty of Vancouver Island. ‘I came to believe as if by osmosis that fishing was my calling . . . I searched for mystery in water.’

During adolescence Hume immersed himself in ‘the world of fly fishing’ celebrated in the books of Haig-Brown, who was still fishing and writing from the banks of the Campbell River before its fishery was depleted—something the famous writer and conservationist did not anticipate. Still Haig-Brown’s many volumes ‘shaped my life and later helped shape the lives of my daughters,’ Hume confirms:

. . . I came to appreciate that fly fishing is more than a hobby; I began to realize that it is a spiritual apprehension, central to the lives of its followers. I knew I had to learn how to fly fish if I was to join that community, if I was to fish in a way that honoured the water and the fish . . . You either have this in your soul or you don’t. It is not taught but is awakened. And once aroused, it became a formative force in my life.

After receiving a fly rod for his sixteenth birthday, Hume fished through his teens for trout, steelhead and salmon among other sports species, before abandoning the activity during his twenties as he travelled about, advancing his career on various newspapers. He married and divorced in quick succession before marrying Maggie, a fellow journalist with a deep love of nature. Despite how good life was with his wife and daughters, Hume was stalked by ‘a distant, unfathomable feeling of despair.’ However, he found solace when he started teaching his daughters, born four years a part, ‘to read the water, to know the natural world.’

The annual family camping trips provided settings for fly fishing instruction. When each of the girls were big enough to manage a nine-foot rod, the initiation commenced. ‘A gifted fly rod is a wonderful thing to have, because a fly rod is as much a talisman as it is a tool,’ Hume observes. ‘When you fish with it, you fish with the love of whoever gave it to you. It becomes infused with memories . . . .’

Angling literature boasts many fine accounts of the piscatorial dynamic between fathers and sons. There are far fewer examples of stories and books celebrating fathers and daughters, which makes Reading the Water as unique as it is exceptional. Readers come to know Emma and Claire as individuals as they acquire not only the methods and techniques, but the ecological aesthetic informing fly fishing. Both learn well from their father, eventually becoming accomplished anglers who cast in time to their own individual rhythms. Following their dad’s example, they attain a ‘higher level of understanding’ after falling under the spell of tying their own flies.

Much has been made of fly fishing’s therapeutic qualities—and deservedly so. Various recovery programs confirm how military veterans and first responders, as well as cancer survivors, benefit from its healing powers. Less acknowledged, however, are the restorative powers of fly fishing in coping with less violent forms of trauma including such common experiences as loss, sorrow and remorse. After all, grief is grief.

Hume discovered that casting a fly line was an efficacious way of dealing with the emotional challenge of his parents’ divorce, including the isolation of his mother and the estrangement of his father. He spent many years in search of surrogate father figures who he found through fly fishing including Haig-Brown and Father Charles Brandt, a trained ornithologist and former Trappist monk who was ordained as a hermit priest while living a half century on the Oyster River. More recently fly fishing played a significant role in Hume’s recovery from prostate cancer.

Although I have read most of Hume’s books and some of his newspaper articles, we have never met. Still, while reading his memoir, I felt like we were sharing the same stretch of holy water, not because of the activity but because of how we view it as a spiritual practice. Although religious sustenance ‘for some is revealed in a bible . . . for others it lies in the cast fly, or in the eye of a fish cradled in their hands,’ Hume offers. ‘In such moments it is possible to experience a meditative state, to reenter the natural world, to understand again how the earth dreams. And that is worth knowing, worth teaching.’

To declare his assertion of faith, Hume has given fly anglers and non-fly anglers alike Reading the Water so they might make up their own minds. All I can say is: Amen.

This book review was written originally for Classic Angling, Great Britain’s premium fishing journal.