This story is set in ‘once upon a time’—BCE or Before Coronavirus Era.

Most fly anglers have secret places. Anglers hold these locations close to fishing vests, like card sharks in high-stakes poker games. These are places of solitude and serenity, with enough resident fish to reward attentive effort and patience. These ‘hidden’ places are sometimes shared with family or with a closed circle of angling companions who swear an oath of secrecy. Dan Kennaley and I have exchanged pledges concerning a couple of piscine gardens.

I recall one time when the location of one of our secret places was compromised. Dan and his brother, Martin, were on their annual trouting adventure in Upstate New York—the West Branch of the Ausable to be exact. Feeling a tad out-of-sorts I decided to spend a few peaceful hours on the Grand River tailwater while awaiting Dan’s return so we could resume our pursuit of early season trout.

I waded to our secret spot and began casting a Hendrickson nymph alongside a current seam where I knew brown trout, some of respectable size, liked to set up house. It was lovely and tranquil in early June. I was alone with my solitude, glad in the glory of the day.

After half an hour or so I heard a commotion downriver. A pair of fishermen were heading my way, thrashing about in their waders and cavorting with every clumsy step. The leader was forging ahead while carrying a rod in each hand. His buddy, following some distance behind, was struggling mightily with a rod in one hand and a large cooler in the other. For some reason, I thought of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza on an angling quest. As they got closer, I detected the sound of beer cans sloshing among chunks of ice.

I don’t want to sound like a fly fishing snob. However, I assumed the intrepid intruders were hard-lure spincasters who, either deliberately or unwittingly, wandered into a restricted angling area (no live bait, catch and release with single barbless hooks). To my surprise, they were carrying fly rods.

‘Catch anything,’ the angler I have named Don inquired upon his approach.

He was not dressed like a ‘typical’ fly fisherman. His chest waders had boots attached. Sans vest and hat, he was wearing a T-shirt boasting a screenprint graphic celebrating an English heavy metal band. His biceps, one of which sported a bold tattoo, confirmed that he was as familiar with barbells as he was with fly rods.

Bulging biceps aside, he had a small fly box tucked into one short sleeve. This reminded me of my childhood in the 1950s when duck-tailed greasers carried packs of filterless cigarettes the same way.

‘Not so far,’ I replied—honestly as it turned out.

‘I caught a twenty-six-incher two nights ago on a Hare’s Ear [nymph],’ Don boasted with unabashed braggadocio, pointing to a riffle a few metres upriver. Although I had no reason to doubt him, I could not vouch for his veracity either. In fairness, I once witnessed trout of comparable size being caught along the same piece of tailwater.

‘Wow, that would be a monster on this river,’ I replied with thinly disguised mock admiration.

Sancho eventually arrived. I smiled and quipped, ‘I see you’re carrying the heavy luggage.’ He nodded with a smile under a sweaty brow.

The two fishermen continued upriver and set up shop on a tiny island adjacent to the riffle that had reputedly delivered the monster. I heard the cooler lid being opened and the refreshing sound of a couple of beer tabs being released. Shfish! Shfish! I imagined thick foamy suds slowly dripping down the frosty sides of the tall-boys.

I resumed casting. A couple of minutes later, I heard a loud bark. It was Don. ‘Fuck, I broke the tip of my fucking rod. I am always doing that. Fuck. Fuck. Fuck.’

I could sympathize, even empathize. I suffered the same indignity a few years previously while gearing up for steelheading. And Dan used a fly rod an inch or two shy of nine-feet for many years after suffering the same mishap.

I resumed casting once again, but the spell of serenity had been shattered. Dan’s and my secret place had been exposed, our lost paradise found out. After a few minutes of billowing frustration I headed back to the Jeep–with, I readily concede, visions of cold beers dancing in my head.

Like most things in life, fishing is diminished by prejudice, stereotype and cliché. There are fly anglers who view spin and bait fishermen as lesser subspecies of anglers. Conversely, there are spin and bait fisherman who view fly anglers as effete tweedy elitists. Neither bias withstands serious scrutiny.

Most fly anglers are not pompous twits with a fetish for Latin entomology. Likewise, most anglers who toss crankbaits from high-octane bass boats are not rednecks in ball caps. And I have seen enough of life to know there are worse things than relaxing under riverside trees and dangling worms with sinkers and bobbers during long lazy summer afternoons—especially if the fisher is joined by his or her grandson or granddaughter.

In A River Why David James Duncan plays with angling stereotypes through the protagonist’s parents. Gus’s father (an English aristocrat who answers to Henning Hale-Orviston and is known to his son as H2O) is an elitist fly angling scribe. In piscatorial contrast, Gus’s foul-mouthed American mom, known affectionately as Hen (as in female steelhead), is an unrepentant bait-tosser who out-fishes her husband by ‘drowning’ worms.

I returned to the newly re-christened not-so-secret piece of tailwater a few times throughout the season—sometimes with, and sometimes without, Dan. The most memorable was the last outing on the cusp of the autumn equinox, a time of magic and synchronicity that invites connection and correspondence.

I tied on an Elkhair Caddis, a popular fly pattern on the Grand because of its healthy population of caddisflies. I cast upriver to a riffle between a pair of weeping willows that stand guard as sentinels over the swirling water. (Yes, this was the riffle where Don allegedly caught his monster.)

I held my breath as a fish broke the surface and inhaled my fly. Time slammed on its brakes and skidded to a sloooooow-motion stop. The world contracted with the snap of a rubber band. My sense of reality was suddenly heightened. My five-weight Sweetgrass bamboo rod arced elegantly, my Cortland double-taper line tightened and my vintage Orvis CFO reel sang a sweet clickety-click melody.

I had hooked a nice brownie. After landing it, I wet my hands and quickly measured the beauty: fourteen inches. A far cry from twenty-six inches, but still breathlessly lovely.

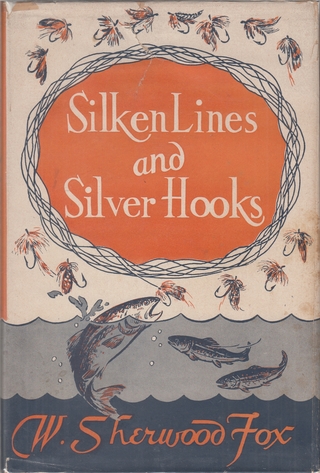

Allowing for the poetic license allowed anglers who equate every inch of fish with two inches of what-might-have been-could-have-been-should-have-been wishful thinking (an exaggeration, perhaps), it conceivably could have been the same brownie Don caught with the Hare’s Ear. After all, I have long taken to heart the words attributed to W. Sherwood Fox in Silken Lines and Silver Hooks when he asks, ‘Are all fishermen liars or do only liars fish?’ only to reply, ‘Of all the liars among mankind, the fisherman is the most trustworthy.’ (I believe this assertion also holds true for angling writers.) No wonder John Gierach, perhaps the world’s most popular contemporary angling writer, titled one of his books All Fisherman Are Liars.

I released the fish, feeling a deep sense of gratitude. The previous day I had exchanged emails with Dan, who was in America’s Big Sky Country with his wife Jan, fishing and attending the annual Norman Maclean festival. They had toured various landmarks associated with the author of A River Runs Through It, including the cabin his father built at Seeley Lake, his family home in Missoula and the Presbyterian church where his father had been preacher—all of which were featured in Robert Redford’s film, starring Brad Pitt as a tragic Hamlet waving a fly rod.

This would have been serendipity enough. Yet it so happens I was reading J. I. Merritt’s Trout Dreams. The book contains an essay on the filming of A River Runs Through It along with thirteen profiles of legendary fly anglers including Al Troth. Living at the time on the Beaverhead River in Dillon, Montana, the eccentric perfectionist invented the Elkhair Caddis, that most Western of dry flies so lethal on the Grand tailwater.